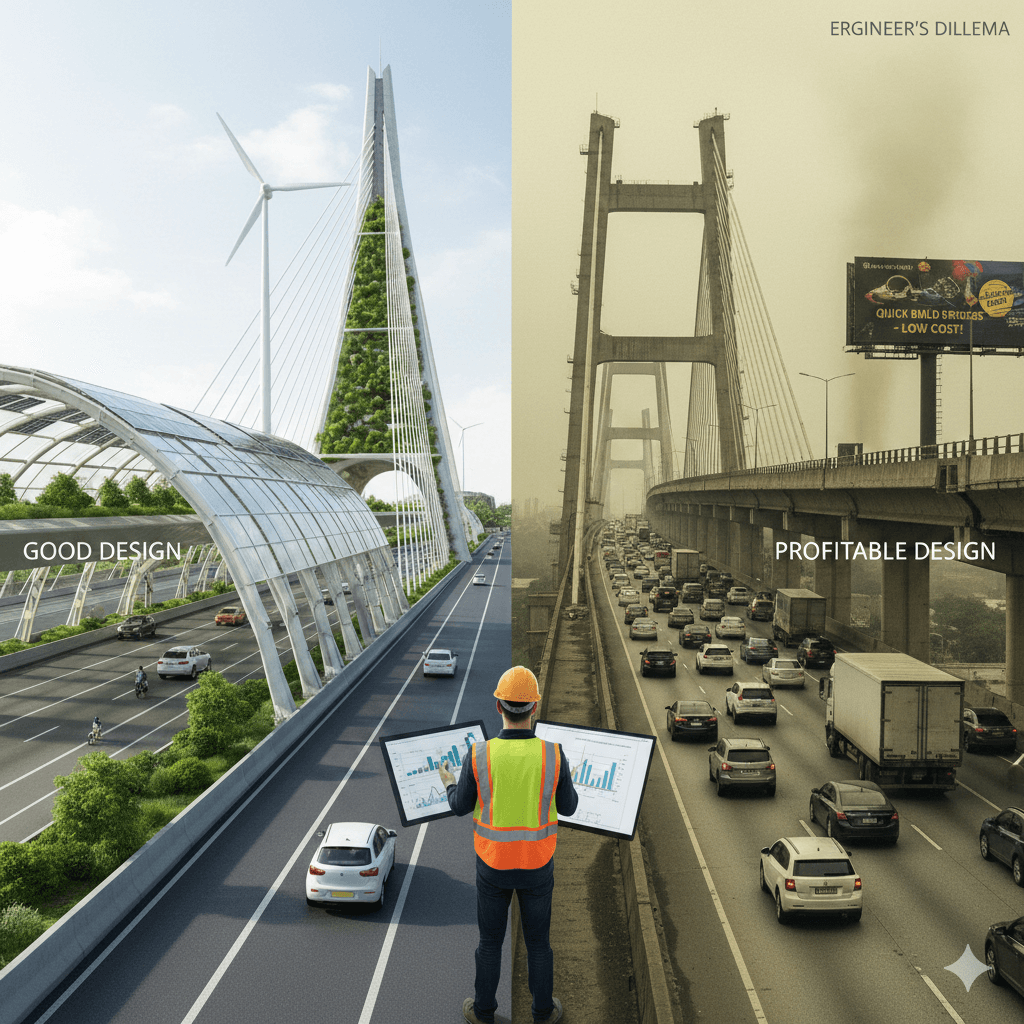

In every field of engineering, from civil to software, there exists a silent tug-of-war: the pursuit of good design versus the necessity of profitable design. Engineers are trained to create solutions that are efficient, safe, sustainable, and user-friendly. Businesses, on the other hand, often prioritize what drives revenue, reduces costs, and maximizes returns for stakeholders. The clash between these two ideals forms what is often referred to as the “engineer’s dilemma.”

At its core, this dilemma is not simply about aesthetics or money. It is about the very philosophy of engineering—balancing technical integrity with commercial viability. Let us unpack the dynamics of this tension.

What is “Good Design”?

For an engineer, good design is one that meets functionality, safety, efficiency, and longevity without compromise. It is a solution crafted with deep attention to detail and foresight, considering not just present needs but also future challenges.

A bridge that is structurally sound, resilient to natural disasters, and requires minimal maintenance is a good design. In software, an application with clean code, intuitive interface, and robust security embodies good design. Essentially, it is the embodiment of engineering ethics and creativity.

Good design is often guided by questions such as:

Will this solution last?

Is it safe for people and the environment?

Does it enhance user experience and reduce long-term costs?

What is “Profitable Design”?

Profitable design, in contrast, is one optimized to maximize financial gain. Here, decisions are influenced by cost-saving measures, return on investment (ROI), and market competitiveness. A profitable design may not always be the “best possible” version from an engineering perspective—it is often the “good enough” version that satisfies consumers at a lower production cost.

For example, a smartphone manufacturer might release a device with average battery life but invest more in marketing to ensure high sales. Similarly, a construction firm may choose cheaper materials that meet safety codes but reduce long-term durability to stay within budget and increase margins.

Profitable design asks:

How can we reduce material and labor costs?

Will this product reach the market faster?

What features do consumers value enough to pay for?

Why the Dilemma Exists

This dilemma arises because engineering operates at the intersection of ethics, innovation, and economics. Engineers aim to uphold technical excellence, while businesses must remain financially sustainable. A purely “good design” may be too costly to implement, pricing it out of reach for the consumer or making the business unviable. Conversely, a purely “profitable design” may compromise quality, leading to long-term risks or reputational damage.

Take the automotive industry as an example. Engineers may want to design vehicles that are fully electric, with top-tier safety features and recyclable components. Yet, producing such vehicles at scale remains expensive, and companies face pressure to maintain affordability and competitiveness. The result is often a compromise—hybrid models or budget versions that meet financial targets but fall short of the ideal.

Consequences of Favoring One Over the Other

When good design dominates: Projects may become financially unfeasible. A product too costly for the market can lead to business failure, leaving the design unused. Think of advanced prototypes that never make it to production because the costs cannot be justified.

When profitable design dominates: Short-term gains may turn into long-term problems. Compromises in durability, safety, or user satisfaction can cause product recalls, reputational harm, or even catastrophic failures. The Boeing 737 MAX crisis is a stark reminder of prioritizing profit-driven timelines over thorough design validation.

Striking the Balance

The real skill lies in harmonizing good design with profitability. This is not easy, but several strategies can help:

- Value Engineering: Instead of cutting corners, engineers and managers collaborate to find creative ways to reduce costs without compromising essential functions.

- Sustainability as Profit: Modern markets increasingly reward eco-friendly and durable products. What once seemed “expensive” in design is now becoming a competitive advantage. Tesla’s electric vehicles or Apple’s emphasis on durability are good examples.

- Iterative Development: Rather than striving for perfection in the first launch, businesses can release functional products and improve them over time. This approach balances financial risk with long-term improvements.

- Ethical Frameworks: Engineers must uphold a non-negotiable baseline of safety and quality. While profit is crucial, human lives and environmental impact must never be traded away.

Conclusion

The engineer’s dilemma—good design versus profitable design—is less a choice of one over the other, and more about finding equilibrium. Good design ensures integrity and trust, while profitable design ensures survival and growth. The future belongs to engineers and businesses that can align these two forces, creating solutions that are both technically excellent and financially viable.

In the end, the true mark of engineering success lies not in perfection or profit alone, but in responsible innovation that serves both society and sustainability.